By Jean-Paul Rodrigue and Theo Notteboom

By Jean-Paul Rodrigue and Theo Notteboom

Shifting Rationale

The interoceanic canals of the global shipping network are undergoing a major upgrading. One year after the expansion of the Suez Canal aimed at facilitating two-way vessel traffic, we are witnessing the opening of a new and larger set of locks at the Panama Canal. The new locks are designed to allow the transfer of ships with a length of up to 366m, a width of 49m and a draft of 15.2m. These New Panamax dimensions are 25% longer, 52% wider and support a draft which is 26% deeper than the old set of locks (Panamax size). In container terms, the new locks are able to accommodate Neo-Panamax container ships with a capacity of 12,000-14,000 TEU compared to an upper limit of 5,200 TEU for the older locks.

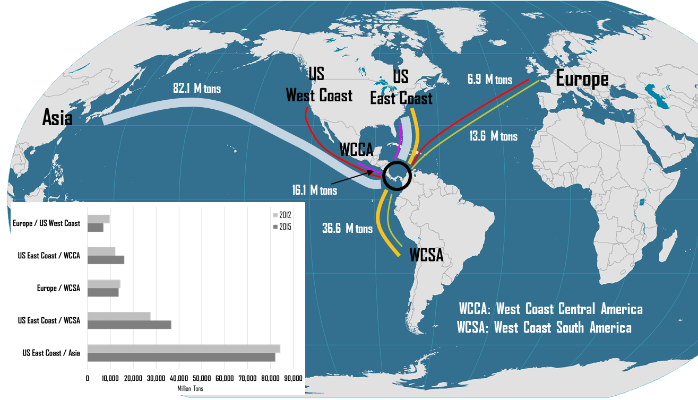

Although the expansion of the Panama Canal is seen as a remarkable engineering achievement, it comes at auspicious times in global trade and shipping. Like many large infrastructure projects, it was built to service a commercial trend that may already have run its course. The opening of the Panama Canal in 1914 was mainly justified to support and expand trade between the US East and West coasts. In subsequent years, commercial changes, the expansion of rail services and the development of the interstate highway system would undermine the relevance of the canal for the American economy. While in 2015 the Panama Canal handled 229 million tons of cargo, American intercoastal trade accounted for less than 1% of this tonnage. Transpacific trade has placed the canal in a new context, with the most significant trade route connecting the US East Coast to Asia (36% of total tonnage), followed by the routes linking the west coast of South America to the US East Coast route (16%).

Particularly, the importance of the Asia / East Coast route mostly justified the Panama Canal expansion project. Trade across the Pacific has become so significant and as ships were becoming significantly larger than the conventional locks, it became imperative that the Panama Canal needed to be expanded. However, the Asia / US East Coast route, even if still dominant, does not indicate significant growth prospects, with its tonnage even declining since 2012. With the expansion, history appears to be repeating itself. While large infrastructure projects such as the Panama Canal expansion might have an impact on the routing of trade flows between regions, their power to influence the magnitude of these trade flows should not be overrated.

A Contested Market

The growth that the Panama Canal experienced in the last two decades was thus driven by specific circumstances mainly related to the transpacific trade. Conventionally, the American East Coast was dominantly serviced through West Coast ports and then overland through intermodal rail services across the continent.

In 2000, this route accounted for more than 80% of the Asian cargo bound to the East Coast. However, this route started to be contested, particularly after a major strike along West Coast ports in 2002, which created significant disruptions and incited traders to find alternatives. Major importers, particularly retailers, started to build distribution centers along the East Coast (e.g. near ports such as Savannah) and booked maritime services transiting through the Panama Canal, known as the “all-water route”. The outcome was a growing share of the Panama Canal route, which reached more than 50% of Asian trade bound to the US East Coast by the mid 2000s. By 2007, several transcontinental rail service contracts were up for renewal at significantly higher rates, which further promoted the competitive advantage of East Coast ports through the all-water route. At the same time the ongoing growth of the Asia-Europe route transiting through the Suez Canal led to the use of Mediterranean transshipment hubs, such as Algeciras and Tanger Med, as competitive options to service East Coast ports.

By 2014, the respective shares of the intermodal rail route, the Panama Canal and the Suez Canal to service the East Coast from East Asia was roughly equivalent. Therefore, in addition to its traditional intermodal rail competitor, the expanded Panama Canal is facing additional competition from the Suez route. The opening of the new Panama Canal locks heralds a new era in route competition. Canal authorities, port authorities and rail operators are increasingly monitoring their competitive position in the global shipping network and adapt their commercial pricing and service strategies accordingly. For example, the Suez Canal Authority is introducing discounts of up to 65% on canal transit tariffs to face increased competition from the Cape route and the Panama Canal route. Future price wars between both canals are possible, as both canal authorities are targeting more vessel transits.

Furthermore, market actors are taking initiatives to limit transit times and increase service reliability. For example, BNSF, one of the main North-American rail operators, is now targeting a reliable transit time of only 70 hours between Los Angeles and the inland hub of Chicago. Shorter transit times and competitive prices are expected to offset some of the competitive pressure exerted by the new Panama Canal locks.

How Footloose is Transshipment?

Another important transformation that took place in Panama in recent years was its emergence as a major transshipment hub for containers. While its ports were handling an insignificant amount of traffic in the 1990s, by the 2010s Panama’s container volumes were the largest in Latin America (close to 7 million TEU, while New York handled 6.3 million TEU in 2015). However, more than 90% of this traffic involves containers that are being transshipped between different shipping services along the Pacific and the Caribbean. Containers are being transshipped in Panama in part because the conventional canal did not allow ships of more than 5,200 TEU to transit; containers carried by larger ships on either the Pacific (mostly) and Caribbean coasts must therefore be transshipped.

The question remains about how convenient and competitive Panama will be for transshipment in the post expansion era. A key element to answer this question is the service configuration of shipping lines and the type of ships they allocate along their routes, which underlines a paradox. US East Coast ports are expanding and dredging with the expectation that larger ships are going to call them directly while Panama is betting that the post-expansion era will involve more transshipment for its ports, even if transshipment has not increased by any significant measure in the last five years.

More Port Capacity on its Way

To fulfill the expectation of more traffic handled by Panamanian ports after the expansion, additional terminal facilities are planned by the Panama Canal Authority. On the Pacific side, the Corozal Container Terminal project has issued a request for proposals to global terminal operators, with four major bidders being retained at the moment. Phase 1 is planned to add 3.2 million TEU in capacity by 2018-19, while phase 2 would add an additional 2.1 million TEU at an unspecified date. Further, the Panama International Terminal, operated by PSA, will be expanding its capacity to 2 million TEU by 2017 (from a current capacity of about half a million TEU).

On the Caribbean side, an agreement was recently reached with a Chinese consortium to build the Panama Colon Container Port, a new post-panamax port facility with a capacity of 2.5 million TEU. All this put together would more than double the capacity of Panamanian ports in the next decade. US East Coast ports are expecting more direct calls, Panama is expecting more transshipment, while other ports in the Caribbean such as Cartagena and Kingston are expecting more transshipment. Something has to give, unless container volumes in the region would unexpectedly see a very significant rise in the coming years.

Expanded Canal, Expanded Trade?

For Panama, larger ships will come with larger port facilities. Will this slack going to be picked up? The engineering of the expanded Panama Canal has little relevance without strong commercial prospects, which are mixed. It is uncertain if the dominant Asia – US East Coast route will show any significant growth and based upon the current commercial context its importance could actually decline. Using larger containerships is not going to generate additional trade by itself, it will simply make it marginally cheaper.

Is this going to be enough for US East Coast ports to gather additional traffic, which they all expect? Additionally, servicing the East Coast has become a highly contested market and the growth of the Suez route could sidetrack many of these assumptions. Economic development in Latin America could increase the amount of intercoastal trade within the region, which could offer notable opportunities. In more than a century since its opening, the commercial function of the Panama Canal has considerably changed and it is expected that it will continue to do so in the post expansion era.