Bottlenecks of global maritime shipping have been for decades the object of geostrategic considerations as obligatory points of passages for global trade. More recently, their geographical advantage inciting the convergence of shipping services in narrow areas has been expanded with the setting of transshipment hubs. This usually involves feeder services towards smaller ports, relays connecting deep-sea services towards different maritime ranges or interlining supporting different port of calls configurations along a similar maritime range. However, based upon geographical and commercial considerations, this clustering of transshipment takes different forms. We provide here a profile of the world’s main bottlenecks and how their respective characteristics shape their transshipment activities.

Panama

With the growth of transpacific trade, the port dynamics around the Panama Canal has substantially evolved but at a different pace and for different factors. Most of the growth took place within Panama and is based on three vectors of maritime connectivity. This first is the one provided by the Panama Canal itself, connecting the Pacific and the Atlantic oceans and thus providing a continuity in deep-sea maritime shipping services. The second and third vectors of connectivity relate to the transshipment functions performed on both the Pacific and Atlantic facades on the canal. The Colon port cluster used to be the main center of activity, but mostly as a domestic port servicing the Colon Free Trade Zone. However, in the early 2000s, the growth in transshipment enabled the setting of Balboa as a new hub, which grew on par with Colon to become the two most important transshipment hubs in the region. Cartagena was also able to become a transshipment hub in the late 2000s, in part due to its accessibility to the Caribbean market and its own national market. Other main ports such as Buenaventura and Puerto Limon grew organically with the dynamism of their hinterlands.

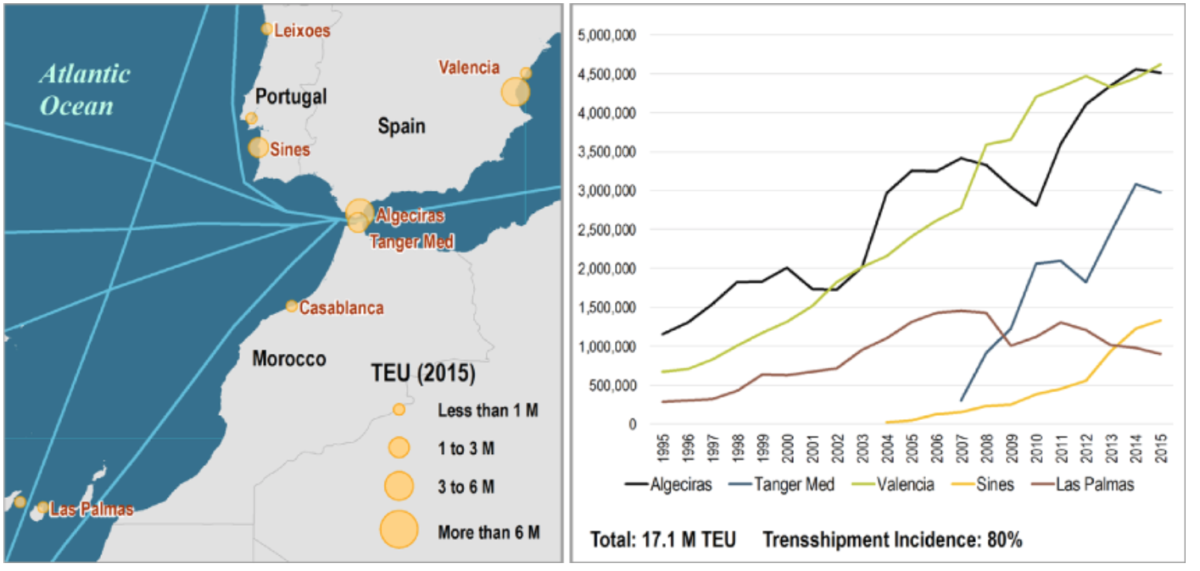

Gibraltar

The Strait of Gibraltar is a natural bottleneck at the junction of Mediterranean, North Atlantic and West African shipping routes. The growth of the Europe / Asia trade has led to the increasing use of the strait for transshipment. Most of this transshipment takes the form of a dual competition between the established hub of Algeciras (on the Spanish side of the strait) and the new hub of Tanger Med (on the Moroccan side). When it opened in the late 2000s, Tanger Med saw the relocation of some of the transshipment activities taking place in Algeciras, but both hubs resumed their growth afterwards, a trend that appears to be leveling off. Both are pure transshipment hubs since more than 90% of their volume concerns transshipment cargoes that do not leave the port. Valencia has also been an active transshipment hub in spite of involving a higher level of deviation from the main shipping lanes since it provides hinterland cargoes as well. The port of Sines in Portugal is also vying for a share of the transshipment business and recently overtook Las Palmas that has been a transshipment hub focusing on the West African trade, a role that has been eroded by Tanger Med.

Suez

With the growth of the Asia-Europe trade, the Suez Canal has experienced a surge in the number of transits and tonnage in the 2000s. This surge has been accompanied by a growth of transshipment activities at Port Said, which is located at the Mediterranean entrance of the canal, and at Jeddah on the Red Sea. This traffic leveled off in the early 2010s. The remaining ports in the region are mostly hinterland ports, some of which vying for a share of the transshipment activity generated around the bottleneck. Still, anchoring transshipment traffic is a complex proposition. For instance, the port of Sokhna (Ain Sokhna) was inaugurated in 2003 on the southern end of the Suez Canal with the expectation of becoming a major transshipment hub, complementing Port Said. However, the port has so far not attracted significant transshipment traffic. Therefore, the connectivity offered by the Suez Canal concerns first its link between the Mediterranean Ocean and the Red Sea, supporting deep-sea shipping services. The second connectivity is the interlining and feeder services calling at the transshipment ports of the Mediterranean facade (mostly Port Said). The third, on the Red Sea side, offers limited feedering and mostly concerns interlining (dominated by Jeddah).

Hormuz

The emergence of the Strait of Hormuz as a transshipment hub is a recent phenomenon since the area was mostly focusing on the oil trade. Economic growth and diversification have been associated with growing cargo volumes around the Persian Gulf, contributing to its insertion as a major trade and logistics platform. Transshipment almost solely focus on Dubai, with Jebel Ali and Khor Fakkan as major facilities, the outcome of massive investment in port infrastructures. Dubai has become a hub for relay and interlining, with feeder services in the Persian Gulf, South Asia and East Africa. The port of Salalah in Oman is also a competing transshipment hub, but its volume has declined in recent years, mainly due to the decisions of shipping lines to use other ports in light of the political instability of nearby Yemen. Other ports in the Persian Gulf, such as Dammam servicing Saudi Arabia and Shahid Rajaee servicing Iran, are hinterland based. The recent decline is Shahid Rajaee, which handles about 80% of Iran’s container trade, is linked with international trade sanctions put in place after 2011.

Malacca

The Strait of Malacca is the world’s most important strategic passage in terms of the volumes it transits; about 30% of the global maritime traffic. Benefiting from its strategic location, the Port of Singapore dominates and has remained the region’s most important transshipment hub, connecting cargoes between Europe / Asia routes. 85% of its traffic concerns transshipment such as regional feeder services as well as relay transshipment between different deep-sea services. However, two major competing hubs have emerged in proximity to Singapore, Tanjung Pelepas and Port Klang (or Port Kelang). The development of these two ports underlines the large demand for transshipment that this passage generates as a point of transit in global trade, a process that appears to be ongoing.

Oresund

The Baltic Sea is accessible through the Strait of Oresund, which gives opportunities for transshipment due to the limited container volumes involved. This role is mainly assumed by Hamburg and Bremerhaven, which are usually the last ports of call for deep-sea services towards Europe. However, their volumes have stabilized in recent years. St. Petersburg is Russia’s most important port, but trade sanctions imposed from 2013 have been associated with a notable decline in traffic. Gdansk emerged as a gateway to Eastern Europe as well as a transshipment hub servicing the Baltic, but again, volumes have been stabilizing. Gothenburg is in a similar situation for Sweden and handles limited transshipment volumes. Other ports in the Baltic are small feeders since there are few direct services out of the Baltic.

A review of the world’s major bottleneck underlines that for the majority of them, the convergence effect that promoted the growth of transshipment appears to have played itself out.