By Jean-Paul Rodrigue

Maritime shipping, more than any other form of transportation, benefits from economies of scale since they have a direct impact on its operational costs. There has thus been a tendency to deploy larger ships, particularly in container shipping, to service high volume trade routes such as between Asia and Europe.

PortEconomics member Jean-Paul Rodrigue comments:

A common issue with the application of economies of scale is that the maritime shipping company is internalizing its benefits since they have a positive impact on its operations, while externalizing many of the costs to other actors along the maritime transport chain. These actors, particularly terminal operators, trucking companies, railways and distributors, are then facing the challenge to mitigate these externalities, often with capital investment projects.

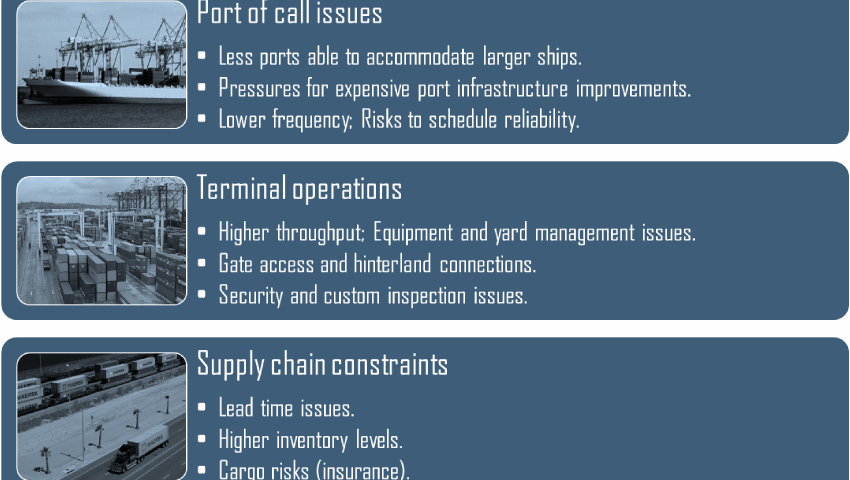

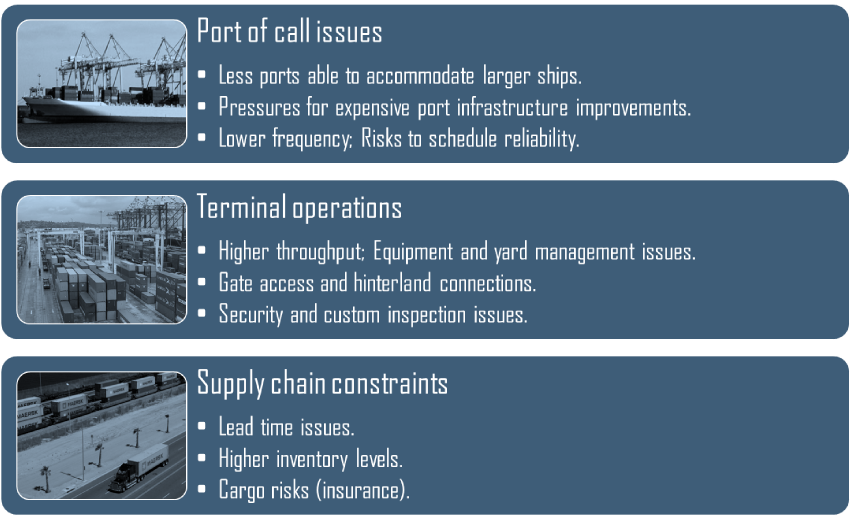

Diseconomies of scale are a common economic concept stating that after a specific level of output the input costs per unit of output are starting to rise. There is thus no incentives to increase the output of the particular unit beyond a threshold. A fundamental issue is that although the concept of diseconomies of scale applies to maritime shipping, port operations and hinterland distribution, it does not involve the same threshold for each. In this hierarchy of scale economies, aritime shipping has the highest potential, followed by terminal operations and then hinterland distribution. Each transport segment cannot be massified to the same extent because of technical, regulatory or operational consideration. As such, the term disadvantages of scale is used mainly because that although the benefits of economies of scale still apply in the maritime segment of the transport chain, these benefits are not well shared with other actors. Some actors may even be negatively impacted by the economies of scale benefiting others. Therefore, the concept of the disadvantages of scale in maritime shipping covers three dimensions:

- Port of call issues. Larger ships require deeper drafts, which can limit the number of ports able to accommodate them. Many ports terminals around the world were built to handle Panamax ships, which has been a standard scale for a century. Less port of call options can limit the commercial appeal of larger ships since their market coverage is more limited, inciting a greater reliance on transshipment. Inlight of this trend, several ports have faced the pressure to invest in infrastructure expansion projects, such as new cranes, yards and dredging port access to deeper drafts (with 50 feet being a common goal). These infrastructure projects are highly capital intensive and may only result in being able to keep a similar amount of traffic being handled. Additionally, larger ships are calling the same ports less frequently and the need to improve their load factor can result in worsened schedule reliability.

- Terminal operations. A way to increase the capacity of a ship is to make it wider, which requires cranes with a deeper reach (a post-panamax ship has between 15 and 23 containers in width as opposed to 13 for a Panamax ship). Further, larger ships require a higher level of terminal throughput since a greater amount of cargo must be handled roughly within the same port call time. This places pressures on terminal operations due to a time compression of the cargo handling, requiring more yard space and equipment. Terminal gate access is also facing constraints as more trucks are entering and exiting the terminal during the same timeframe. Fares that are paid by maritime shipping companies, such as port fees, are essentially remaining the same on a per TEU basis, implying that the terminal operator does not necessarily see a growth in its revenue with larger ships. Capital investment in infrastructure, often assumed by publically owned port authorities, are therefore even more difficult to amortize. Larger ships could actually involve a decline in terminal capacity because of the time compression of cargo operations larger ships impose.

- Supply chain constraints. These external issues are often neglected when considering the impacts of using larger containerships since they concern beneficial cargo owners not involved in transport operations, but in supply chain management. The coordination of supply chains can be impacted in a significant manner, since a lower frequency of port calls imply the necessity to hold higher inventory levels, both in warehouses and in transit. For instance, an importer facing decreasing port of call frequency, would be forced to maintain a higher inventory level in its distribution centers to maintain a similar average lead time and meet the expectations of its customers. More cargo being carried on a single ship also represents a greater risk for partial loss or damage, particularly near ports, involving higher insurance premiums. Still, the risk factors of mega containerships remain to be better assessed by the insurance industry.

All of the above underline ongoing discrepancies between maritime operations, terminal operations, hinterland distribution and supply chain management. Maritime shipping companies appear to be the only beneficiary of economies of scale in ship size. If the disadvantages of scale for the other actors in the transport chain are taken into account, the economic benefits of larger containerships maybe limited. Still, economies of scale are contingent upon the trade routes, the port of call sequence and even the general nature of the cargo being carried. There is thus no standard optimal ship size.

Please cite as: Jean-Paul Rodrigue (2015). The Disadvantages of Scale in Maritime Shipping. Redistributed via www.PortEconomics.eu. Originally published at http://people.hofstra.edu/geotrans/eng/ch3en/conc3en/Disadvantages_Scale.html