By Ricardo J. Sánchez[1], Daniel E. Perrotti[2] & Ma. Alejandra Gómez-Paz Fort[3][4]

In the business of containerised cargo international logistics, which connects domestic and global economies, the ships’ sizes have direct implications in the decision-making process for logistics and trade. Business, financial, operational, and public decisions on infrastructure, logistics services, and territorial planning partly revolve around issues such as the size and technology of ships and the allocation of resources that shipping companies decide for their fleets.

The progressive increase in the size of container ships, at different rates over the last 20 years, has been studied by the authors of this article both globally and regionally in South America. The objective of the studies has been linked not only to the understanding of the phenomenon but also to promote tools for decision making that leads to the development of sustainable infrastructures.

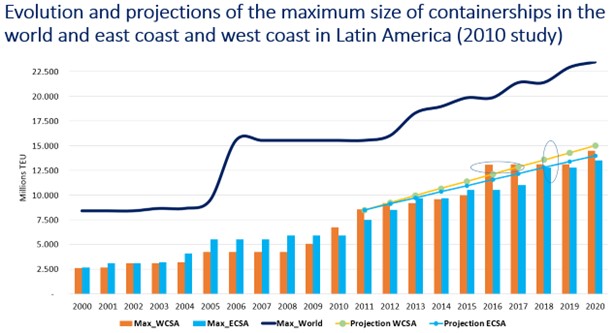

In this sense, Sanchez and Perrotti (2011) studied the phenomenon in 2009 and estimated the potential arrival date of large container ships in South America.[5]

The estimations were made using econometric models with pooled data that used the vessels’ nominal capacity (in teu) as a dependent variable. The explanatory variables used were port activity (measured in teu) and the gap between the maximum size (in teu or length, LOA) of the ships that arrived in South America and those that simultaneously sailed through the main trade routes, among other variables. The currently trending “cascading” effect is at the base of the model used, which shows that it is not a new phenomenon.

Moreover, Gómez Paz (2013) used a prospective method based on a semi-quantitative Delphi methodology (expert consensus) and a quantitative model (dynamic model, “predictive game”) to project future scenarios and found that the size of the ships was limited mainly by the depth of the channels and dredging in the ports and that other factors such as the new CO2 restriction measures, the price of oil, some economic factors, the costs per unit of transport and the concentration of the shipping lines, drove the trend towards larger ships, altering the balance between supply and demand. The survey results showed that ships with a capacity of up to 26,500 teu would arrive by 2032.

With time, it has been possible to verify that model’s predictions were accurate. This behaviour can be seen in the following graph, which highlights that the 2011 projections were in line with the evolution observed in the sector.

Given the acceleration in the growth of the global median size of fleets (due to the appearance of MX-24 series vessels) and the accuracy of the projections of the 2011 article, in 2019 Sanchez, Perrotti, and Gomez Paz (2020) updated the study (https://rb.gy/oc8do), with new predictions about the arrival of larger ships to the coasts of South America. Furthermore, the models were expanded with an additional dependent variable: length overall. Therefore, the predictions followed two guidelines: a) the nominal capacity, considering a target vessel of 18,000 teu and b) a length of 1310 feet.

Regarding the new projections, the authors assumed a historical scenario (with the explanatory variables based on the observed historical trend), an optimistic scenario (with an average increase on both coasts of around 10% in port activity concerning the historical trend), and two negative scenarios (which projected a reduction in port activity of between 10% and 30% on average for both coasts).

The results of the projections that were more accurate with the actual behaviour of the explanatory variables conclude that for the west coast of South America (WCSA), the 18,000 teu ships would arrive in 2025, and for the east coast, by 2027. The study was carried out a few months before the pandemic’s start; in this sense, the impact that the COVID-19 crisis had on the economy and logistics impacted the assumptions that the authors used in the study. However, this does not necessarily imply a significant delay in the arrival of these ships. While the arrival may no longer be in 2025, it will be near 2025.

The recent arrival of the MSC Chiyo to the WCSA, deployed on the Far East-West Coast of South America route, is proof of this: the ship was built this year, of 170,500 DWT, 1310 feet of LOA, 20 rows at beam and 17 m of draft, with a nominal load capacity of 16,550 teu. In generic terms, this is a stage before the 18,000 teu study ship, placing the prediction between 2024 and 2027.

However, the prediction has been blunt concerning the length, as demonstrated by the announcement of the arrival of the CMA CGM Alexander von Humboldt ship, built in 2013, with a capacity to transport 16,000 teu and a length of 1,300 feet.

In short, the predictions have been quite accurate in both the first article and the second when contrasted with the empirical evidence regarding the arrival of giant ships to the coasts of South America.

However, such results do not automatically imply an urgency to build new, larger ports to stay integrated with the maritime transport network. This is because the decision to invest in new ports must be prudent, as it is an irreversible, sunk cost of enormous magnitude.

Based on these projections and empirical behaviour, the authors are more prone to recommend that policymakers be more attentive to and proactive in investments in intensive technology and new port practices, which replace part of what was previously solved with construction. Eventually, the option of “moving the port” to recent locations and facilities will naturally arrive.

Likewise, a strong dynamism has been observed in recent years regarding the rotations of liner services, conditioned by port infrastructure and logistics services –dimensions of infrastructure and reliability in operations– and by the cargo that attracts vessels, by volume, balance, and seasonality. On the other hand, it is also true that the role of ports has changed significantly in recent decades, so port decisions must be strongly oriented towards their integration into the supply chain and industry development.

It is necessary to reconsider an old principle: ships go where two conditions are met, sufficient cargo to move and the ports have the conditions required to receive the vessels. This means that the mere increase in the size of ships does not automatically imply that ports must grow at the same rate if demand (cargo) does not justify it. Still, port authorities do have to be very attentive to the industry’s evolution.

For these reasons, the difference that is currently observed between the east and west coasts of South America can be understood. The west coast is where the model’s forecasts have been fulfilled perfectly in both predictive stages, with full precision between 2010 and 2023, while on the east coast it was fulfilled until 2018 and then there was a delay. At a quick glance, it is possible to attribute the reason to the lack of sufficient ports with the necessary capacity and demand on the east coast.

References:

Gomez Paz, Maria Alejandra, Camarero Orive, Alberto & González Cancelas, Nicoletta (2015): Use of the Delphi method to determine the constraints that affect the future size of large container ships; Maritime Policy & Management Volume 42, 2015 – Issue 3; Routledge; https://doi.org/10.1080/03088839.2013.870358

Gomez Paz (2013): “Diseño y aplicación de una metodología prospectiva para la determinación de los condicionantes futuros del crecimiento de los grandes buques portacontenedores”, Tesis (Doctoral), E.T.S.I. Caminos, Canales y Puertos (UPM). https://oa.upm.es/20924/

Sánchez, Perrotti, and Gomez-Paz (2021): Looking into the future ten years later: big full containerships and their arrival to South American ports; Journal of Shipping and Trade 6, 2 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41072-021-00083-5

Sánchez, Perrotti & Gomez Paz (2020): Ongoing challenges to ports: the increasing size of container ships. FAL Bulletin 379; United Nations – ECLAC. https://hdl.handle.net/11362/46457

https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/46027/1/S2000486_es.pdf

Sanchez y Montiel (2016): Big vessels are here, the time left to act is shrinking; Maritime & Logistics Bulletin 59; United Nations – ECLAC. https://www.cepal.org/sites/default/files/news/files/boletin_maritimo_59_january2016_eng.pdf

Sánchez and Perrotti (2012): Looking into the future: big full containerships and their arrival to South American ports, Maritime Policy & Management, 39:6, 571-588, DOI: 10.1080/03088839.2012.729697 https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/03088839.2012.729697?needAccess=true

[1] Co-chair, Kühne Professorial Chair in Logistics, School of Management, Universidad de los Andes, Colombia; Head, Caribbean Research Institute, Caribbean Shipping Association; and Porteconomics.eu, associate member.

[2] United Nations, ECLAC

[3] Member, Kühne Professorial Chair in Logistics, School of Management, Universidad de los Andes, Colombia

[4] Any views, thoughts, and opinions expressed here are solely that of the authors and do not reflect necessarily the views, opinions, policies, or position of any of their affiliations.

[5] See https://rb.gy/fuwv4 and https://www.cepal.org/sites/default/files/news/files/boletin_maritimo_59_january2016_eng.pdf