By Jean-Paul Rodrigue

The current global manufacturing landscape is the outcome of successive waves of innovation and economic development and their geographical accumulation. Although the industrial revolution is often considered as a single ongoing event that began in the late 18th century, it can be better understood as four sequential paradigm shifts, or four industrial revolutions. Each revolution built upon the innovations of the prior revolution and lead to more advanced forms of manufacturing.

PortEconomics member Jean-Paul Rodrigue comments:

The first industrial revolution in the late 18th and early 19th century focused on the benefits of mechanization where for the first time some animal or human labor could be substituted by mechanical labor. New forms of manufacturing activities emerged, creating industrial cities of various functions (steel, textiles, tools, etc.).

The second industrial revolution in the late 19th and early 20th century relied on the application of the principle of mass production along assembly lines, which was able to scale up manufacturing output. This further incited a level of specialization and interdependence in manufacturing, which mainly took form in industrial regions (or manufacturing belts).

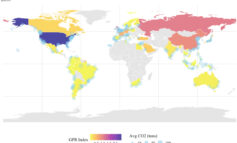

The third industrial revolution that took place in the later part of the 20th century benefited from the ongoing automation of several manufacturing processes, while at the same time globalization (as an outcome of trade liberalization and lower transport costs) enabled a minimization of input costs, particularly related to labor, and thus to a new manufacturing landscape. Since these costs are not ubiquitous, this incited the setting of global production networks where manufacturing activities tried to minimize input costs while logistics and transportation enabled to support the spatial differentiation of production and consumption. This process was very disruptive to the existing manufacturing landscape, including the closure of manufacturing facilities.

The fourth industrial revolution is unfolding and is mostly based on robotization (with supporting IT structures), which confers a higher level of flexibility in terms of the locations, the manufacturing processes, the scale and scope of the output, and the customization of the products. In such of context, the importance of input costs, particularly labor, are rebalanced since labor can be considered close to ubiquitous for manufacturing relying of robotization. The focus therefore shifts on global value chains, which are a sequential process used by corporations within a production system to gather resources, transform them in parts and products and, finally, distribute finished goods to markets. Manufacturing and supply chain management become closely embedded.

Manufacturing is often considered as a separate activity from distribution since most manufacturing activities are trying to minimize input costs (e.g. labor) while distribution activities are trying to maximize market accessibility. This is particularly the case for distribution activities related to finished goods. However, globalization, particularly the resulting international division of production, has reinforced the importance of distribution capabilities to support the geographical and functional complexity of value chains.

Since a growing aspect of manufacturing becomes less dependent on basic inputs costs such as labor and land (as a total share of added value), the flexibility of manufacturing is more related to access to suppliers and customers. Under such circumstances, areas having access to global and regional distribution systems accumulate an important advantage (or component) in the fourth industrial revolution. Flexibility relies on the concept of flow and as such logistics zones (freight distribution clusters) are expected to assume a growing share of manufacturing.

In time, this is favoring the emergence of a new manufacturing landscape where production and distribution capabilities are closely embedded. Since logistics is a highly transport related activity, logistics zones nearby large terminal facilities such as ports, airports and intermodal rail yards, are offering an attractive proposition for the emerging manufacturing landscape. This case study will look at the role of logistics zones can play in manufacturing and provide some examples about how this is taking place.