Chinese container ports are feeling the full impact of the Chinese economic slowdown and the weak global economic situation. Over the years, we have become used to seeing high growth rates in Chinese ports, so the sudden change might come as a bit of surprise to many. How significant is the slowdown in container throughput in Chinese gateways and how do the figures compare to the situation in other key container port regions around the world?

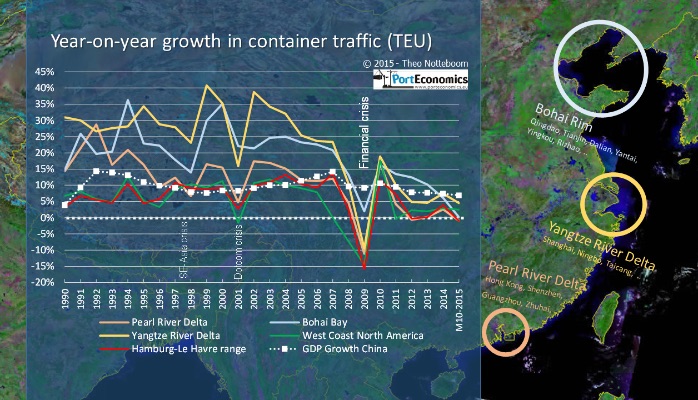

The infographic shows the year-on-year growth in container throughput in the three main container port regions in China (i.e. Yangtze River Delta, Pearl River Delta and the Bohai Rim). Two key trading partners of China are also included: the port system along the North American West Coast including ports such as Seattle/Tacoma, Vancouver, LA, Long Beach and Oakland; and the Hamburg-Le Havre port range consisting of key north-European container ports such as Rotterdam, Antwerp, Hamburg, Bremerhaven, Le Havre, Zeebrugge and Wilhelmshaven. We conclude the following.

First, the Pearl River Delta (Hong Kong, Guangzhou, Shenzhen and many others) shows a much lower growth rate than the two other Chinese port regions. Since 2004, its growth pattern is very similar to the one observed in the Hamburg-Le Havre range. Actually, after the financial crisis year 2009 year-on-year growth in the Pearl River Delta is even slightly weaker than in the considered European and North American port systems. In particular, the traffic position of Hong Kong is getting weaker since 2009 with a further decline of 8.7% in the first ten months of 2015. The port is expected to handle about 20 million TEU in 2015, compared to 24.24 million TEU in record year 2008. Even Shenzhen is witnessing a much lower volume increase this year with only +2% up to October 2015.

Second, the Yangtze River Delta recorded elevated annual growth rates of 15 to 40% before the economic crisis. Since 2011, container volumes increase by a much more modest 4 to 7% per annum. The first ten months of 2015 show a growth of ‘only’ 4.5% with Shanghai +3.3%, Ningbo +6.9% and higher growth rates for river ports Nanjing and Suzhou.

Third, the Bohai Bay region is considered as one of the fastest rising container regions in the world. However, its growth pattern shows a sudden and strong downward trend since 2013. In the first ten months of 2015 container traffic even stagnated at +0.2% with Tianjin (-2.8%; partly because of the blast earlier this year) and Dalian (-2.1%) showing the weakest figures. With this result, the (former) rising star of the Chinese container port system is positioning itself among more mature port regions such as the Pearl River Delta and the Hamburg-Le Havre range (-1% mainly caused by traffic decline in Zeebrugge, Hamburg and Bremerhaven). The North American West Coast recorded +2.5% in the same period thanks to the 5 to 6% growth figures in Seattle/Tacoma, Vancouver and Long Beach and a strong growth in Prince Rupert, which overcompensated the traffic decline in Los Angeles and Oakland.

Fourth, the relationship between GDP growth and container growth in China is changing. For a very long time, the GDP multiplier was well above one, meaning that any increase in the GDP coincided with a much higher container throughput growth. In the past five years, the GDP multiplier is consistently below one for most of the port regions in China. This supports the notion that the Chinese economy is going through a transition phase with more focus on the services sector and a growing dependency on domestic demand instead of external trade.

Overall, 2015 promises to become a weak year in the container port industry. Contrary to the temporary slowdowns observed during the Southeast Asian crisis (1997-1998), the Dotcom crisis (2001) and even the financial crisis (late 2008-2009), the volume slowdown of the past five years is visible in all port regions considered and seems to be of a more structural nature. Obviously, not all ports face the same situation. In a fairly stagnant market, you can only grow by taking volumes from your rivals. This leaves room for port users to play off one port against the other. The resulting intensified port competition is leading to stronger growth differences between adjacent ports, as can be observed in port regions in Europe, the US and China. No wonder that port cooperation has become such a hot topic, also in China.