by Thanos Pallis

published in Naftemporiki (ed). Focus on Shipping, 28 Sept, 2023

Chinese investments in European seaports have increased rapidly in the 21st century. This increase is part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – in particular, its maritime component, the Maritime Silk Road (MSR) – and is among the economic and geopolitical effects of China’s growing role in global affairs.

Seaports are crucial pivots connecting a national economy with the world economy. Historically, however, China was a land power; its presence in ports or port terminals is a relatively new phenomenon that has advanced its transformation to one of the largest seaport constructors and operators in the world. The Maritime Silk Road, put forward in 2013, stretches from the Pacific to the Atlantic through the trajectory of the Indian Ocean, Eastern Africa and the Mediterranean Sea, connecting about 50 marine countries of Southeast Asia, South Asia, West Asia, North and Eastern Africa, Southern European countries, and the Maghreb states.

The BRI project aims to connect countries for commercial and cultural purposes through rail, sea, pipeline and road. As part of this goal, China has invested in two-thirds of the world’s largest container ports, with this presence continuing to expand. A distinguishing characteristic is that this strategy unfolds without being necessarily tied to governance-related conditionally; it often involves development projects contracted to Chinese companies. Its main way of funding is through bank loans granted by a mix of government, state-owned enterprises (SOEs), development agencies and private institutions. According to data firm Refinitiv, 60% of the BRI projects are owned by [Chinese] government entities, while the private sector accounts for about 25%.

Investments mainly aimed at gaining control of particular port infrastructures and this has led to some critical approaches. Mostly these are infrastructures that are critical to certain markets or trades in order to establish and consolidate a «leverage» over global and regional supply chains, at the same time creating the conditions to absorb the Chinese industrial over-capacity. To China, BRI consists of a broad set of “policy coordination” to learn from the Chinese experience and know-how while serving the goal of its exports having easy access to the European market.

For the countries hosting seaports, the benefits of Chinese investments are not limited to economic and political rewards generated by the broader cooperation with a leading economy of the world. In terms of capacity, China stands among the prominent “empires” of seaport operations. Throughout the last two decades, China has ranked first in the world in tangible goods trade. its trade and container throughput has ranked top of the world. Ports ‘at home’ have been instrumental in the global economy. Among the world’s top -20 ports in terms of global trade throughput, or the respective list of the leading container ports in terms of throughput mainland 13 ports are Chinese.

A key role in the presence of Chinese interests in the global port industry has been China Cosco Shipping. The national shipping company which was founded as a state-owned enterprise in 1961, established its first international presence in the late 1980s and became the first Chinese company to be enrolled as a member of the World Economic Forum in 2000, has invested in several ports around the globe. The linkages of the leading liner shipping company with one of the three alliances (ONE) transporting containers should not be underestimated, as allowing a carrier to participate in a container terminal is one of the best guarantees to attract vessel calls and volumes to the ports. Today, together with China Merchants Port, which is another Chinese maritime financial group, the share of the world’s total capacity corresponds to approximately 24% of the TEUs handled by container ports annually.

In Europe (Table 1), the presence spans seven countries, including its main European partner, Germany, with which China trades goods valued at almost €300 billion per annum. Notably, all Chinese investments in the continent – and beyond – are via the purchase of minority/majority stakes in container terminal operations. The sole exception is Greece which has offered the opportunity to purchase the majority of the managing entity of Piraeus port and determine the present and future of the port.

| Port (country) | Type of Investment | Shares | Investor | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antwerp (Belgium) | Container Terminal | 25% | China Cosco Shipping | 2004 |

| Piraeus (Greece) | Container Terminal | Concession | China Cosco Shipping | 2008 |

| Marseille (France) | Terminal Link | 49% | China Merchant Group Intl | 2013 |

| Zeebrugge (Belgium) | Container Terminal | 24% | China Cosco Shipping | 2014 |

| Rotterdam (The Netherlands) | Container Terminal | 35% | China Cosco Shipping | 2016 |

| Vado Ligure (Italy) | Container Terminal | 40% | China Cosco Shipping | 2016 |

| Vado Ligure (Italy) | Container Terminal | 9.9% | Qingdao Port Intl | 2016 |

| Piraeus (Greece) | Purchase of Port Authority | 67% | China Cosco Shipping | 2016 |

| Zeebrugge (Belgium) | Container Terminal | 76% | China Cosco Shipping | 2017 |

| Bilbao (Spain) | Container Terminal | 51% | China Cosco Shipping | 2017 |

| Valencia (Spain) | Container Terminal | 51% | China Cosco Shipping | 2017 |

| Hamburg (Germany) | Container Terminal | 24.99% | China Cosco Shipping | 2023 |

As regards other parts of the world, in the Pacific, the Chinese presence ranges from North Korea (Port Rajin) to Malaysia (Melaka Gateway) and Australia (Port Darwin). At the Bay of Bengal, Chinese presence in operating and/or constructing ports includes Myanmar (Kyaukpyu), Sri Lanka (Hambantota; Port Colombo), and Bangladesh (Chittagong). In Southwest Asia, the list includes Pakistan (Gwadar), Saudi Arabia (Jeddah Port), Abu Dhabi, the UAE (Khalifa Port) and Oman. In Eastern Africa, one might name Kenya, Sudan, and Tanzania. In Maghreb, it includes Alegria, Morocco and in the non-European Med the presence ranges from Egypt (Damietta, Suez) to Turkey (Kumport).

Investing in Greece: Piraeus

Although China has made numerous maritime investments abroad in recent years throughout the world, few have attracted as much attention as its acquisition of the Piraeus Port in Greece. Following a failed attempt for a direct intergovernmental agreement in 2006, which was rejected by the European Commission on grounds that it lacked an international open tender, Piraeus Container Terminal (PCT) SA was awarded the right to operate container terminal Pier II and construct a new Pier III in 2008. This concession was followed by the decision of the Greek State to sell the majority of the stakes of the Port of Piraeus Authority in 2016, with China Cosco Shipping purchasing 67% of the PPA SA shares, following an international tender.

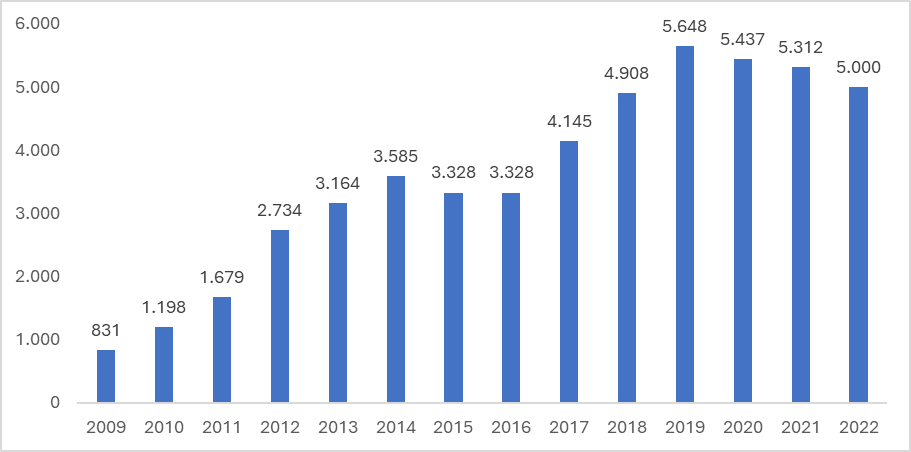

Since 2008 the levels of containers handled in Piraeus have increased to record levels, as has done its liner shipping connectivity. Piraeus is today a major transhipment hub, with the port standing as the fifth-biggest container port in Europe (following Rotterdam, Antwerp-Bruges and Valencia) and as the third in the Med (after Valencia and Tangier Med). Notably, Chinese investments occur in all these major container ports.

The most advanced BRI port projects so far are those that are based on existing routes. BRI projects representing success stories for China include Piraeus an expansion of existing ports along established maritime routes. Other port projects along similar lines include the acquisition of the terminal portfolio of Noatum, most importantly its terminal in Valencia. Less progress has been made on projects related to alternative routes. BRI projects that are related to new trade opportunities, in particular in Africa, seem to be promising, especially when port projects are linked to railway development towards hinterlands and mineral resources. New canal projects – such as the Nicaragua and Kra canals – do not seem likely to materialise. Although it cannot be excluded that the coming decades will see the emergence of alternative maritime routes driven by these projects, their likelihood is not very high.

The challenge

China extends its commercial investments overseas underscoring the principle of development first. Seaport projects provide the conditions through which the Chinese government is cautious in going global without threatening the status quo of specific countries. In general, China seeks economic opportunities through involvement in owning, operating, or developing commercial seaports contending that they offer win-win for both the investor and the hosting country.

This process has triggered a debate in Europe on the significance of, and how to deal with, growing Chinese influence in European ports. Over recent years, the commercial involvement by Chinese firms in European ports has become increasingly politicised. The main driver of this process is the changing perception of China in some parts of Europe. Whereas ten years ago, China was regarded primarily as an opportunity for economic exchange, some European governments are increasingly focusing on the potential risks related to interaction with China. The minority presence of Cosco in the smallest terminal of the port of Hamburg had been subject to controversy before the German government gave its approval in early 2023. As is more the case, when Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are involved or when these activities take place in strategically important sectors, such as ports, decision-makers are not ready to provide an a priori approval – while at large due to the extensive presence of Chinese interests in European ports, the European Parliament is considering guidelines for a uniform involvement of foreign direct investors in ports around Europe.

In any case, with ports standing as the critical infrastructure for local, regional, national and global prosperity China’s participation in seaport operations and management serves as the symbol of achievement of a leading global economic power.