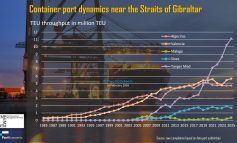

As container ships grow ever larger to achieve greater economies of scale and hence cost savings, ports expand to be able to handle them. This expansion occurs both in terms of the physical size of berths and the speed and efficiency of handling the large drops of containers that must be moved in and out of the port gate and through the hinterland. Port systems evolve according to these trends, resulting in a concentration of container movements at a handful of hub ports within each range, and flows are then feedered to other ports according to a variety of schedules devised by carriers to balance their vessels and containers.

Feeder ports generate enough cargo to require shipping services but not enough to require large vessels. They remain sufficiently distant from larger ports in the same range that under current market conditions the larger ports cannot serve this hinterland profitably overland. So smaller ports continue to serve their local markets, connected to transhipment-only or hybrid ports by small feeder vessels. They generally possess limited water depth and handling facilities, as large investments required to handle larger vessels are not justified by their low container throughput. How long will this situation continue? Are current trends for larger vessels likely to threaten this model? Will smaller vessels disappear entirely, meaning that small ports will lose their connections unless they upgrade their facilities? Or will shipping lines continue to serve these ports via the insertion of second-tier hub ports where cargo is transhipped from large to small feeder? While there are several demand-side influences on port systems such as the global economy and regional trade specialisations, one of the main supply-side influences is the supply of shipping services.

Ports invest large sums upgrading their facilities and competing to receive calls from the new ultra-large container ships entering service, but handling such demand spikes is difficult. The larger the vessel and the larger the drop of containers at each call, the larger the knock-on effect in terms of unreliability on the rest of the container system. The Asia-Europe trade remains the driver for the largest class of container vessels, and while increased traffic on other trades induces expectations that they will be served by larger vessels in future, there is some evidence that larger vessels are being cascaded too soon, simply because of the carriers’ need to soak up excess tonnage, leading to dramatic underutilisation on some routes.

In addition to the need to employ excess tonnage, regulatory influences that lead to increased fuel price (e.g. SECA regulations requiring the use of more expensive low sulphur fuel or the use of scrubbers) will also encourage the cascading trend, as such investments are better spread over more containers hence fewer, larger ships are desirable. Also, owners of older smaller feeders will be reluctant to invest in upgrading them so they will be moved elsewhere and newer feeders introduced are likely to be larger. In addition, busy ports handling large vessels prefer not to occupy valuable berth space with small feeder vessels.

From the perspective of small ports, cascading of vessels presents a much more serious problem. If even medium traffic routes can expect to be served by vessels too large for their traffic, the case is even more acute for the trades below them, continuing down to 2-4,000 TEU routes, and, finally, to small feeder routes currently served by sub-1,000 TEU vessels.

16% of the world sub-1,000 TEU fleet is currently laid up. This represents 50% (in terms of number of vessels) of the total supply of vessels laid up, demonstrating that such vessels are the last choice to utilise if other vessels can be employed first. Moreover, the average age of these vessels is 15 years. Many of these vessels, particularly in the sub-500 TEU range, are nearing the end of their lives, meaning that they will be phased out soon. As very few sub-1,000 TEU vessels are on order, this suggests that larger feeders with deeper drafts seem certain to serve at least some of these routes. The majority of vessels on order (in terms of TEU capacity) are in the range of the largest vessels, which will exert significant pressure to cascade medium-sized vessels downwards. The 1,000-2,999 TEU range remains the most numerous (in terms of number of vessels) in both the current world fleet and the order book; using these vessels on smaller routes will grant increased flexibility to operators. But with 90 active container ports (21% of world container ports currently being served by sub-1,000 TEU vessels) having berth depth of less than 9.1m and the need to accommodate design drafts of at least 8.7m, larger vessels will threaten the viability of these ports unless they commit significant investment. Depth is the key metric in many port expansions although of course berth length is also important as is access infrastructure such as locks which are not uncommon in small ports.

It seems likely that, just as container ports at the larger end of the scale were rationalised as flows concentrated at major hubs, several drivers exist for the same process to occur at small ports. Ports that do not upgrade may lose their connections entirely or local shippers may be required to pay for an additional handling cost to tranship a second time from large feeder to small feeder, or perhaps they will be forced to rely on overland transport links. Even if the port finds the finance to upgrade, there will be fewer calls. Ceteris paribus, doubling the vessel size would halve the number of calls, although in reality the reduction would probably not go as far as that. Many smaller ports only attract a handful of container vessel calls per week. Is it viable to remain open for fewer calls? In addition, less frequent calls will place limitations on the supply chains of local shippers, leading to increased costs through the need to increase inventories. The penalty of peripherality, already suffered by many producers and consumers not located on the main trade lanes, may soon grow worse. Consequently, planners and policymakers responsible for such ports should be considering now how they will resolve these challenges on behalf of their local shippers.