By Jean-Paul Rodrigue

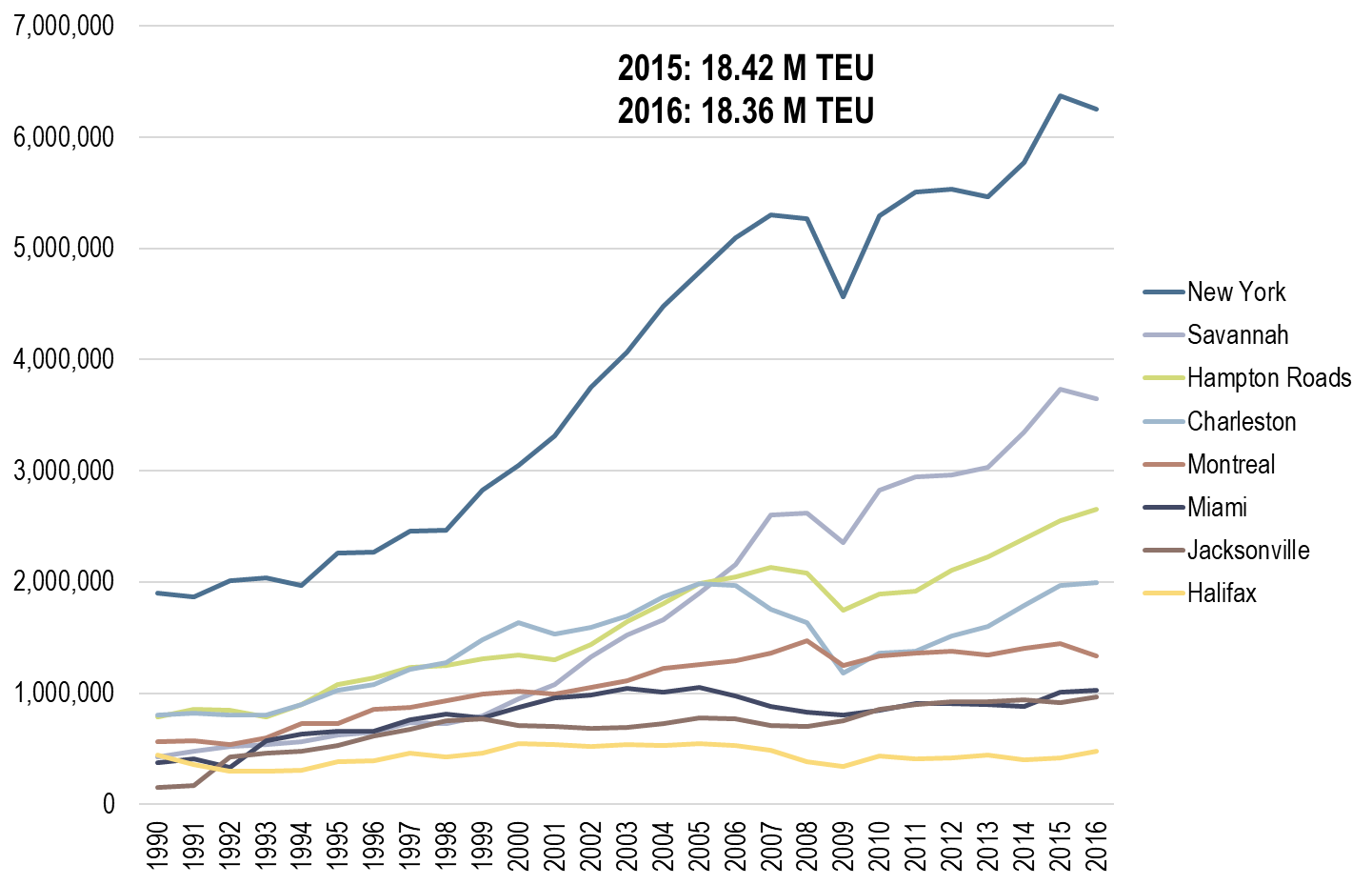

The expansion of the Panama Canal in 2016 has been hailed as a remarkable achievement and a game changer for the shipping industry, particularly for the North American East Coast and the Caribbean. It would be accompanied with higher levels of port activity and therefore the need to invest and upgrade port infrastructure, including dredging. However, the expectations of higher container volumes transiting through the region have so far not materialized and actually the throughput of key East Coast ports has on average declined between 2015 and 2016. For instance, eight large container ports on the Eastern Seaboard saw a slight decline in their collective volume from 18.42 million TEU in 2015 to 18.36 million TEU in 2016 (see Figure 1). At this stage, the expansion provides limited evidence of significant shifts in container cargo throughput, which is contradicting the expectations that many American port authorities were conveying prior to the expansion to justify additional infrastructure investments.

Figure 1: TEU Handled by Selected East Coast Ports, 1990-2016.

What is shifting is how this cargo is transported, namely the operational and capacity impacts of introducing rather suddenly larger ships from the standard 5,000 TEU Panamax vessel to which most of the terminal facilities of the region are optimized to handle. The Post-Panamax ships, particularly those reaching what is known as Neo-Panamax (about 12,000 TEU), have the perverse effect of tying up additional terminal capacity, effectively reducing it, while not necessarily bringing additional traffic. Terminals in this situation are facing the unpleasant and rather unforeseen outcome of having to invest in additional equipment and modify operations simply to keep a similar level of service. This adaptation can be labeled as the “Post-Panamax syndrome”.

Cartagena; disruptions and adaptation

The port of Cartagena in Colombia is particularly illustrative of this effect because of its proximity to the Panama Canal and its role as a major transshipment hub as well as the main gateway to Colombia. After the expansion, the terminal operator of two of its major container terminals, Manga and Contecar, had to undertake a disruptive transition, including the purchase of 6 super post Panamax cranes (two at Manga and four at Contecar) in order to cope with the operational changes and bring back the dynamic capacity it was losing as the frequency of Post-Panamax ship calls was increasing. The existing Post-Panamax cranes can reach 19 containers across, but this the utmost technical limit, while a few of the smaller Panamax cranes can only reach 17 or 18 containers across (see Photo 1).

Photo 1: Neo-Panamax ship with 19 containers across. This crane can only reach 17 or 18 containers across

The six new cranes that are about to come online can reach 24 containers across, enabling to more efficiently service Neo-Panamax ships of 19 or 20 containers across. As a greater share of the port calls (and total carried volume) shift to post-Panamax vessels, adding cranes has the perverse outcome of not necessarily adding any significant capacity, but enabling the terminals to adjust to external factors imposed by the shipping industry and undertake a transition to new service configurations.

This transition remains unclear in terms of how many Post-Panamax ships are going to service the region and which ports they will call. Paradoxically, the throughput handled by Cartagena has not increased much, and even declined in 2016. The port (SPRC and Contecar) handled 2.16 million TEU in 2014, 2.38 million TEU in 2015 and 2.29 million TEU in 2016. The 3.4% decline between 2015 and 2016 is in spite of the expansion of the Panama Canal, a trend that appears unchanged so far for 2017 (see Figure 2). Thus, similar to its East Coast counterparts, the port of Cartagena is contemplating rather limited growth prospects but changes in the nature of ship calls.

Figure 2: Monthly TEU at the Main Terminals of the Port of Cartagena, 2014-2017 (Note: the change in mid 2015 is related to a major shipping line switching its calls from Manga to Contecar)

To better understand the implications of larger container ships on port terminals, the approach can be divided in three main parts. The first relates to the maritime / port interface (berth and crane operations), the second relates to yard operations and the third relates to gate / hinterland operations.